Mokume Gane, Japanese Unique Wedding bands and Engagement rings

- 949-629-8174(USA) 81-90-9625-2928(Others)

- english@mokumeganeya.com

Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 26 : Ancient lucky item made by Mokume Gane

Modern living has seen a reduction in the use of the Toko no Ma (decorative alcove) space in homes, with it disappearing completely from some, but the practice of offering up “kagami mochi” round rice cakes at the new year remains entrenched, doesn’t it? These are offered to “Toshigami-Sama” or the gods of the incoming year, and by eating the mochi that are infused with the power of the gods, one prays for happiness in the coming year. Since olden times, the designs that are associated with happiness in Japan have been incorporated into clothing and accessories, being considered auspicious. Decorating one’s home with such items expressed a wish to invite happiness in. The little embossing mallets that we are introducing in this chapter are among these lucky designs.

The good luck mallet is well-known as a tool carried by the god Daikoku. Daikoku is one of the seven gods of luck, and it is he who brings wealth to people. He holds a little embossing mallet in his right hand, and in his left hand, he carries a large bag containing treasure and happiness. It is said that every time he hits something with the mallet, coins pour out, which is why he is the symbol of wealth and prosperity.

These little mallets are often made of wood, but the ones we are featuring this time are made of Mokume-Gane and are truly gorgeous pieces fashioned with gold and silver inlay. Both the small and large models have handles made of copper, shakudo and shibuichi (an alloy of silver and copper) yielding a three-colored striped Mokume-Gane pattern. The larger mallet has inlays representing a pair of crows which symbolize matrimonial harmony, as well as a turtle symbolizing a long life. This mallet is 22 cm long and 9.5 centimeters wide. Within these limited dimensions, the representations of the crows and turtle are truly brought to life. The combination with the bolder Mokume-Gane patterns makes the gorgeousness of the ornaments stand out. Both the large and small mallets are also decorated with gold and silver representations of a mouse (“Nezumi)” which is said to be Daikoku’s Familiar, as a sign that they are good luck mallets. These highly auspicious works are a real delight to the beholder’s eye.

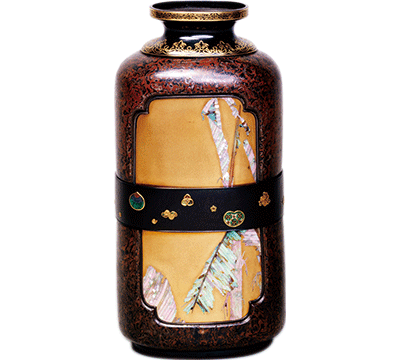

Both mallets were made during the Meiji Era. Following the Haitôrei (sword prohibition) Edict, Mokume Gane had moved away from a technique mainly used for making tsuba, to the manufacture of everyday objects such as brush cases and pipes. In more recent times, the quality of the decorative aspect led to its use in the production of ornamental artworks such as the vase from the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum which we introduced in a previous issue. Used as the base for the foundation of the work, Mokume Gane came into its own in enhancing the ornamental effect by bringing out the other decorations that were added, while ensuring overall harmony.

Nowadays, it is possible to print process detailed shades of color, patterns and designs on all types of materials other than metals. But in the days when such technologies did not exist, the advent of Mokume Gane which made it possible to create materials with organic and variable patterns, was doubtless something of a revolution.