Mokume Gane, Japanese Unique Wedding bands and Engagement rings

- 949-629-8174(USA) 81-90-9625-2928(Others)

- english@mokumeganeya.com

Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 26 : Ancient lucky item made by Mokume Gane

Modern living has seen a reduction in the use of the Toko no Ma (decorative alcove) space in homes, with it disappearing completely from some, but the practice of offering up “kagami mochi” round rice cakes at the new year remains entrenched, doesn’t it? These are offered to “Toshigami-Sama” or the gods of the incoming year, and by eating the mochi that are infused with the power of the gods, one prays for happiness in the coming year. Since olden times, the designs that are associated with happiness in Japan have been incorporated into clothing and accessories, being considered auspicious. Decorating one’s home with such items expressed a wish to invite happiness in. The little embossing mallets that we are introducing in this chapter are among these lucky designs.

The good luck mallet is well-known as a tool carried by the god Daikoku. Daikoku is one of the seven gods of luck, and it is he who brings wealth to people. He holds a little embossing mallet in his right hand, and in his left hand, he carries a large bag containing treasure and happiness. It is said that every time he hits something with the mallet, coins pour out, which is why he is the symbol of wealth and prosperity.

These little mallets are often made of wood, but the ones we are featuring this time are made of Mokume-Gane and are truly gorgeous pieces fashioned with gold and silver inlay. Both the small and large models have handles made of copper, shakudo and shibuichi (an alloy of silver and copper) yielding a three-colored striped Mokume-Gane pattern. The larger mallet has inlays representing a pair of crows which symbolize matrimonial harmony, as well as a turtle symbolizing a long life. This mallet is 22 cm long and 9.5 centimeters wide. Within these limited dimensions, the representations of the crows and turtle are truly brought to life. The combination with the bolder Mokume-Gane patterns makes the gorgeousness of the ornaments stand out. Both the large and small mallets are also decorated with gold and silver representations of a mouse (“Nezumi)” which is said to be Daikoku’s Familiar, as a sign that they are good luck mallets. These highly auspicious works are a real delight to the beholder’s eye.

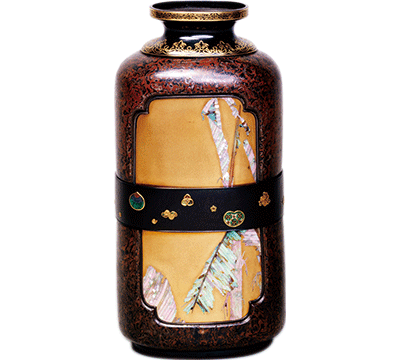

Both mallets were made during the Meiji Era. Following the Haitôrei (sword prohibition) Edict, Mokume Gane had moved away from a technique mainly used for making tsuba, to the manufacture of everyday objects such as brush cases and pipes. In more recent times, the quality of the decorative aspect led to its use in the production of ornamental artworks such as the vase from the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum which we introduced in a previous issue. Used as the base for the foundation of the work, Mokume Gane came into its own in enhancing the ornamental effect by bringing out the other decorations that were added, while ensuring overall harmony.

Nowadays, it is possible to print process detailed shades of color, patterns and designs on all types of materials other than metals. But in the days when such technologies did not exist, the advent of Mokume Gane which made it possible to create materials with organic and variable patterns, was doubtless something of a revolution.

Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 25 : Exhibition of an introduction to the World of Sword Fittings

The Osaka Museum of History which stands right next to the majestic Osaka Castle recently held a “Special Exhibition in Commemoration of the Donation of the Katsuya Sword-Fitting Collection: The Definitive Introduction to the World of Sword Fittings.”

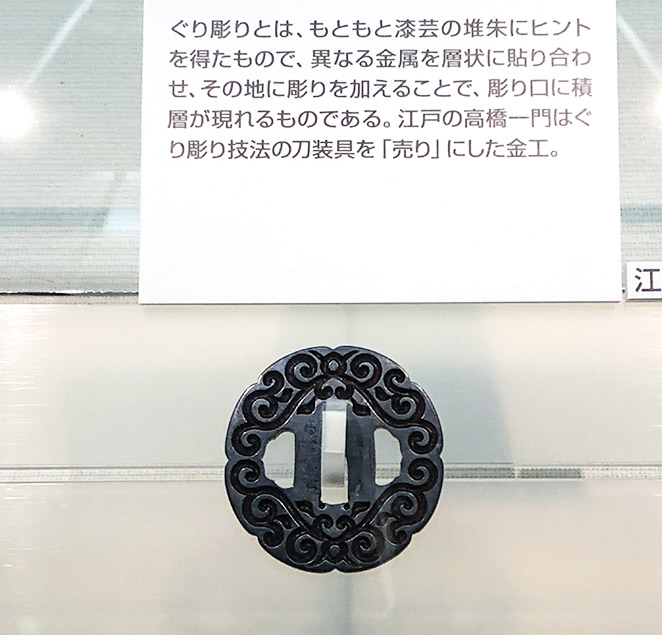

The museum exhibited around 200 pieces from the 927 piece collection of Katsuya Shunichi (1895-1980), who was a renowned collector and student of swords during the Showa Era, and which were donated to the museum by his heirs. There was also a segment introducing the sword fittings of Sakai Toshimasa, a metalsmith who was designated an intangible cultural property by the Osaka Municipal Government. It so happens that matching metal fittings in guribori made by the famed Takahashi Masatsugu in the Edo Period had been gifted by Sakai Toshimasa to the Mokumegane research Institute. And so we went to visit the exhibition which we will describe below.

It is rare to have the opportunity to view as many as 200 “tsuba” sword fittings at the same time, and as the exhibition was presented as “an introduction to appreciation,” there were, under the headings of “what are sword fittings?” detailed explanations of every portion of the sword, as broken down from every possible angle. We were able to speak with curator Naoko Naito who had curated this special exhibition, speculating on how Katsuya Shunichi had, within the framework of his research, built up his collection, and how it had then been reconstituted and exhibited.

There were introductions of the various base materials such as iron and copper, and an area for understanding the meanings behind the various designs that made up the patterns, as well as a presentation of the differing regional styles depending on the metalwork in various parts of the Japan during the Edo period. Takahashi Okitsugu was the representative artist for Edo and his guribori tsuba from the Mokumegane Research Institute was also on display.

During the Edo period, some metalsmiths were in the employ of various warrior clans in order to meet their needs, leading to the development of various regional techniques and designs for making tsuba.

As you doubtless know, since both the front and back of a tsuba are visible once it has been fitted onto a sword, there is a design on both sides. The exhibition curator, Ms. Naito was very creative in how the items were displayed in order for visitors to truly appreciate this. The way the exhibition was laid out, so that it was possible to see the designs both on the front and the back made it possible for people to appreciate the wit that was an integral part of the work of Edo craftsmen. Without any doubt, this was an unmatched offering with a plethora of small sword fittings and beautifully preserved decorative items that one could never grow tired of looking at.

Aside from the tsuba, there were also numerous other items on show such as kozuka, fuchi and kashira, with thorough explanations, including a very rare wooden kozuka.

The exhibition was so much fun that one emerged feeling that one had become an expert in sword fittings after touring it. On the day of our visit, there was also an interesting lecture on sword fittings by Dr. Minami Asuka, a professor at Sagami Women’s University. To our astonishment, she talked about the mention of Mokume Gane in a 1915 book published overseas on Japanese crafts, which made us very happy. We will talk more about that subject at a later date.

The exhibition ran from October 5 to December 1, 2019.

http://www.mus-his.city.osaka.jp/eng/exhibitions/special/2019/tousougu.html

Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 24 : Reproduction work of a famous Mokume-Gane sword tsuba

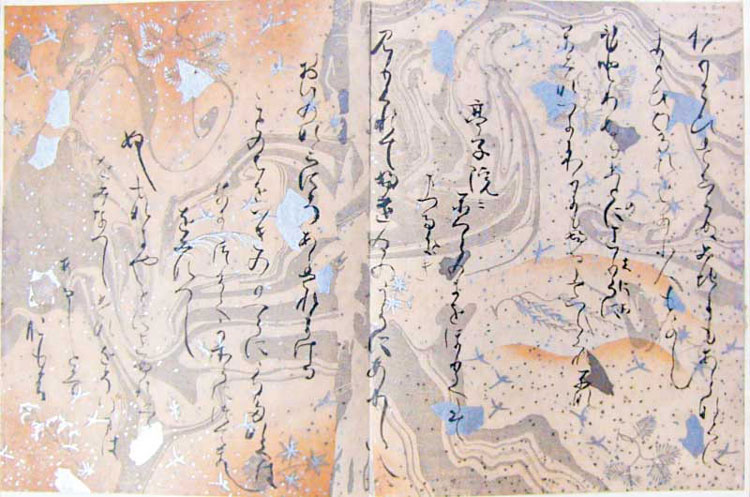

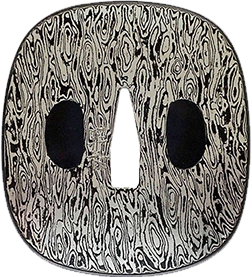

This is an octagonal tsuba that is refined and presents a feminine elegance. In ancient Japan, the number eight was auspicious and regarded as a “sacred number”. It was also considered to be a well-balanced and steady shape that represented all directions (as in fortunetelling). The exquisite Mokume Gane pattern stretches out over one side of the elegant octagonal tsuba. It is as though fine and intricate lines had been drawn on the red base of copper, in a marbling effect. The black part is in shakudo (an alloy of copper and gold) and the Mokume-Gane was achieved by using a chisel to carve out the multilayered surface of copper and shakudo. Since the shakudo used in the layering was quite a bit thinner than the copper, the final effect once it had been flattened was that of fine marbling (suminagashi).

This is an octagonal tsuba that is refined and presents a feminine elegance. In ancient Japan, the number eight was auspicious and regarded as a “sacred number”. It was also considered to be a well-balanced and steady shape that represented all directions (as in fortunetelling). The exquisite Mokume Gane pattern stretches out over one side of the elegant octagonal tsuba. It is as though fine and intricate lines had been drawn on the red base of copper, in a marbling effect. The black part is in shakudo (an alloy of copper and gold) and the Mokume-Gane was achieved by using a chisel to carve out the multilayered surface of copper and shakudo. Since the shakudo used in the layering was quite a bit thinner than the copper, the final effect once it had been flattened was that of fine marbling (suminagashi).

Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 23 : Mokume Gane tsuba with the image of “Moon and Rabbit”

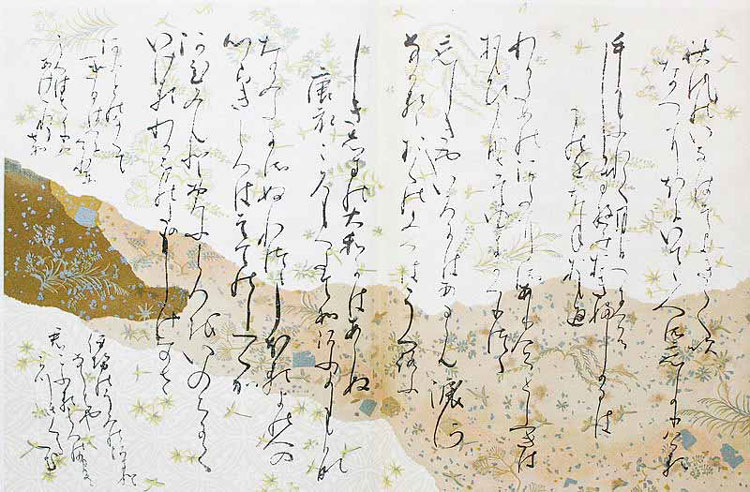

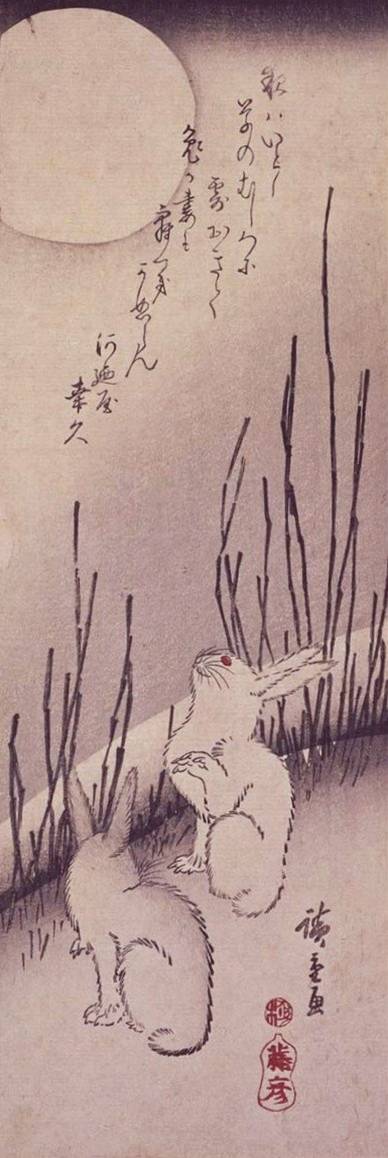

The mid-autumn harvest moon this year was on September 13. We hope you were able to admire it. One of the traditional images of the moon in Japan shows a rabbit pounding mochi, and this has, since ancient times, often been used as an image in the world of Japanese crafts. One of these images does not depict the moon itself but combines the rabbit with other designs to create a perception of the moon.

Scouring Brush (Tokusa) Rreeds and Rabbits

Rabbits by some scouring brush reeds. Starting in the 18th century, there were many cases of works depicting this particular combination.

It is said that the origin lies in Zeami’s Noh song “Tokusa”: “The autumn moon, as if brightly polished, shines through the trees of Mt. Sonohara, where the scouring brush reeds are harvested.” When this song is depicted in a art, the fact of painting an image of a rabbit, which is associated with the “brightly polished moon”, that is to say the full moon, enables the artist to hint at the moon without actually showing it.

In this Mokume Gane tsuba, which is part of Mokumeganeya’s collection, are depicted Tokusa reeds and rabbits looking upward. At first glance, it looks like the only use of an intricate Mokume Gane pattern is in the portion around the hole and which therefore cannot be seen once the blade is fitted. But in fact, the entire tsuba is made from bicolored Mokume Gane, combining copper and Shakudo. The surface finish is black, representing the darkness of night. But depending on the angle at which one shines a light on it, the underlying Mokume Gane pattern becomes slightly visible. It is likely that the craftsman who made the tsuba used this technique to hint at the surroundings in the moonlight rather than convey total darkness. Beyond the rabbits looking up at the moon, the moon itself was doubtless shining brightly. Mokume Gane comes into play to depict the background, rather than just show a simple pattern.

The brush reeds and rabbits are made three-dimensional through metal inlay using gold and silver, and the additional very fine line engraving on the surface of the brush reeds and rabbits emphasizes their delicate texture further. The red coloring on the rabbits’ eyes both makes the rabbits look cute and adds to the charm of the piece.

The quality of the metalwork in a tsuba that is less than 7cm in diameter is extremely fine. In this piece, the Mokume Gane technique, while being secondary, plays a major role in depicting the subject.

Finally, we would like to introduce the ukiyo-e print of “Rabbits and Reeds in the Moonlight” by Utagawa Hiroshige which is in the collection of the Tokyo National Museum. In this case, the full moon is depicted, with the rabbits looking up at it.. It is interesting to compare this image to that of the tsuba.

Mokume Gane Wedding Rings: Reddot & iF Design Award READ MORE >>

Mokume Gane Engagement Rings READ MORE >>

Mokume Gane Wedding Bands READ MORE >>

Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 22 : Various shapes of Mokume Gane

The technique of Mokume-Gane came from the techniques for manufacturing tsuba (sword guards).

From the time when swords were used as weapons, through the peaceful world of the Edo period, there was a strong inclination for sword accessories to be seen by warriors as an expression of themselves and of their individuality. This is how highly decorative tsuba came to be made, and the intricate patterns made from Mokume Gane came to be used.

The very shape of tsuba depended on the taste of its owner. In olden times, people did not just pick a shape as a simple design, but rather were moved by the belief that certain shapes were auspicious for them. We will introduce here Mokume Gane tsuba and the meaning of their shapes.

“Marugata” round-shaped

This is the shape that is most often used in tsuba. As the circular shape signifies “completion” or a “lack of angles,” its positive meaning is liked by many.

“Mokkôgata” lobed (quince)-shaped

The name comes from a resemblance with the cross-section of a quince. The appeal of the quince comes from it giving a great deal of fruit, and since it also resembles a bird’s nest, it has long been appreciated for its connotations of a prosperous progeny. It comes in four, five and six segment variants.

“Aorigata” saddle-flap shaped

The “aori” were leather pieces that would hang down from a horse’s saddle to offer protection from mud. This was a shape that was familiar to warriors and that is why it was used as a tsuba shape. It is a solid shape, with the lower part being somewhat wider than the upper part.

“Gunbaigata” Military fan-shaped

Long been believed to ward off demons and call down mysterious powers, the fan shape has also been used in Shinto rituals. In addition, it is said to be an auspicious shape that shows the right direction to move forward, just like brandishing the military fan led the way to victory.

“Kikubanagata” chrysanthemum flower-shaped

Since the Edo period, September 9th has been designated “Chôyô no Sekku” or Chrysanthemum Festival, in which chrysanthemum sake is drunk while praying for long life. For the Japanese, the chrysanthemum is a very familiar flower with good connotations.

“Hakkaku” octagonal-shaped

In ancient Japan, 8 was considered a “sacred number” that was very auspicious. It is also a stable and well-balanced shape that incorporates all 8 directions used in divination.

There are also various other shapes of tsuba, and all of them are said to be auspicious, and one can imagine how important it was for ancient people to wear them on their person.

At Mokumeganeya, we consider ourselves the heirs of those ancient people and their wishes and so produce “tsuba jewelry” using the popular “Yottsumokkôgata” shape handed down from the Edo period.

Mokume Gane Wedding Rings: Reddot & iF Design Award READ MORE >>

Mokume Gane Engagement Rings READ MORE >>

Mokume Gane Wedding Bands READ MORE >>

Find “Mokume Gane” Special Edition : Mokume Gane watch of SEIKO’s highest-end Credor brand

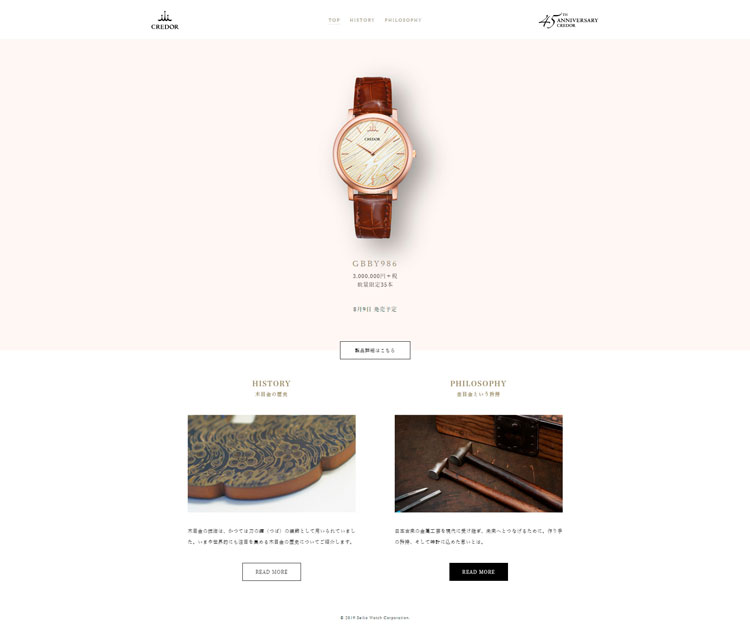

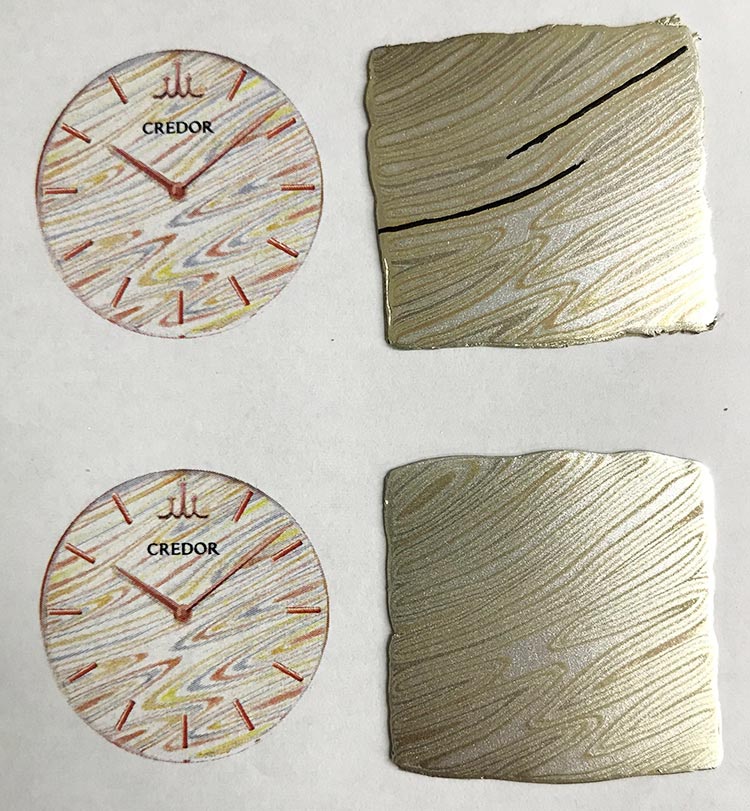

For those of you visiting Mokume Gane Fairs, we would like to let you know that, in addition to jewelry, you might be interested in purchasing our wristwatches. We recently put on the market a watch with a dial made of mokume gane. Mokumeganeya collaborated with the Seiko Watch orporation to produce a limited edition model as the “45th Brand Launch Anniversary Commemorative Model” of Seiko’s highest-end Credor brand.

There is a special “Mokume Gane Direct” page on the Credor website, with the following text:

“ Credor is celebrating its 45th anniversary.

To mark this event, we have produced a decorative dial made using mokume gane, a metal-working technique dating back to the Edo period.

The multicolored patterns that are produced using this technique, which originated and evolved in Japan, convey both beauty and eternity.”

The craftsmanship that has been cultivated in over a hundred years of Seiko’s history is based on a brand concept in which existing traditional watch-making techniques are treasured whilst simultaneously offering new styles. The aim is to produce designs that distill the essence of the Japanese sense of beauty while holding world-wide appeal. Already in the past, the company has marketed models that made use of traditional lacquer techniques with mother-of-pearl and gold lacquer on black japanned bases.

The design concept of the mokume gane dial is known as “Kazemoku,” depicting the profoundly Japanese landscape of ears of rice fluttering in the wind. The original design is a sublimation in design of a rich, golden-hued landscape.

In the past, during the Edo period, the great tsuba craftsman Takahashi Okitsugu produced mokume gane designs for tsuba that depicted “red maple leaves swirling in the Tatsuta River” and “cherry blossoms floating in the Yoshino River.” The flowing rivers represented the passing of time. In this particular case, the unseen “wind” is depicted in the tiny world of the watch dial which itself visualizes time.

Here are some more details on the production of this dial, which was a first for Mokumeganeya.

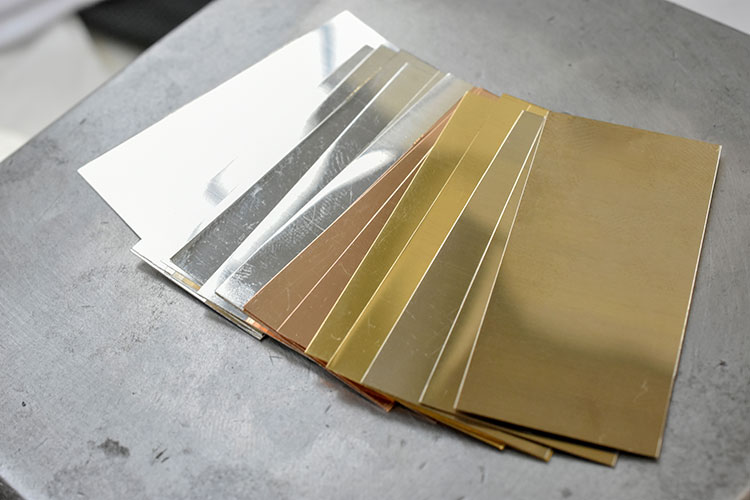

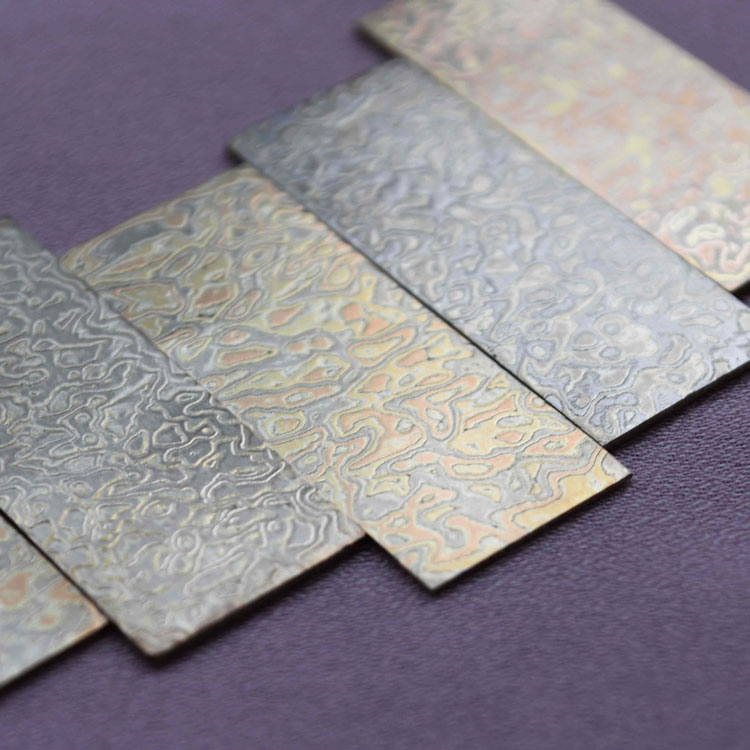

The Mokume Gane used in the dial is made of 18 carat white, yellow and pink gold, plus silver.

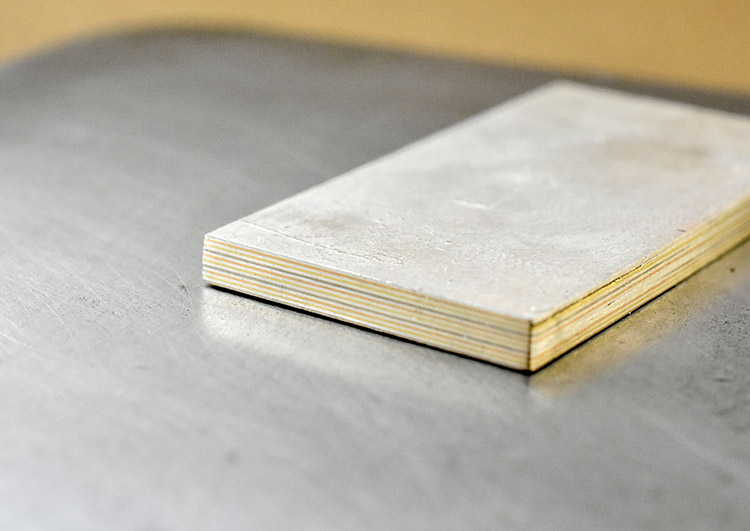

The various colored plates were stacked keeping in mind the desired pattern in the final product once the metal has been flattened. These stacked plates are bigger than the ones used to manufacture rings, and there are more of them, so particular care needed to be given to the fusion.

The thickness of each plate is between 0.15mm and 0.2mm. They were stacked and then underwent diffusion bonding in an electric furnace.

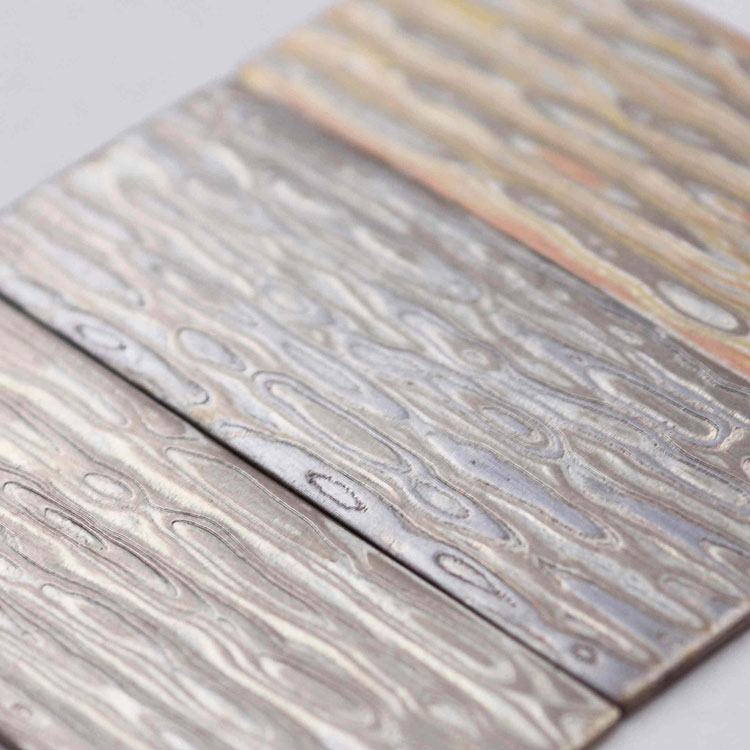

Each billet was shaved down by hand using a Leutor tool. As the depth of the shaving changes, the color that comes to the surface changes, so the design is achieved by alternating shaving, heating and flattening.

The plate that finally becomes the dial is 0.8mm thick. In order to achieve the perfect design with that particular thickness, great care had to be taken in the repetition of shaving and flattening.

The plate was cut to the round shape and size of the dial, and it was then polished so as to make the pattern stand out. It was then complete.

Following this, the watch was assembled by Seiko Watch Corporation. The ultra-thin hand-winding “Gulliver 6890” movement was fitted into the 18 carat pink gold case. The total thickness being only 1.98mm, the highly-skilled watchmakers could only assemble one or two units per day. The final product is a superb masterpiece which is the handmade fruit of the labor of highly-skilled craftsmen.

This collaborative product presents a different level of difficulty in comparison to the wedding rings produced by Mokumeganeya. We discussed this with the craftsmen concerned.

Test Production

In order to achieve the desired design image once the metal had been flattened, it was necessary to repeat the process of fusing and shaving many times while changing the thickness of the stack of sheets 0.05mm at a time. As the surface was limited to the size of the dial, the thickness was set at 0.8mm and if the stack was shaved down too much, the traces of the shaving would be visible when the desired thickness was achieved. But overly shallow shaving would yield a monotone effect. The thickness of the silver or gold, depending on their position in the stack, would alter the design effect. It’s almost impossible to count how many tests were done before achieving the final product.

The Design

Since this is handmade, the exact same design cannot be achieved twice, and the uniqueness of each design is the charm of Mokume Gane, but on this occasion, it was necessary to achieve a uniform design is order to preserve the “Kazemoku” pattern. Since the pattern would change if there was even a slight over-shaving of the surface, special effort was made to keep the angle of the blade constant.

The Finish

The surface underwent a frosting process, but with the particularity of Mokume Gane coming from the use of different metals, irregularities can easily appear when the surface is processed. Also, as the surface is much bigger than in rings, it was a challenge to achieve a uniform impression.

Also, normally, there is no surface processing, but as the product this time was the dial of a watch, part of a precision instrument, it was necessary to ensure that it was perfectly flat. The thickness of the finished product was 0.8mm. It required a great deal of effort in terms of roller work and press processing to achieve a completely flat surface on extra-thin sheets made of metals of different hardness.

This product marketing collaboration came about after someone at the Seiko Watch Corporation saw an interview with Mokumeganeya President Takahashi in the Nihon Keizai Shimbun newspaper. That article was written because a Nihon Keizai Shimbun journalist had purchased wedding rings from Mokumeganeya. The journalist was very interested in the pursuit of Mokume Gane by Takahashi, and interviewed him.

The efforts to replicate the Mokume Gane products from the Edo period, and to develop this traditional technique further into something that is relevant to the modern world have yielded another new product.

The “Mokume Gane Dial” has been available at Credor Salons and Credor Shops in Japan since August 9th, 2019. As numbers are very limited (35 watches in all), please contact the store ahead of time.

https://www.credor.com/shop/

More detailed informational is available on the Seiko Watch Corporation website at

https://www.credor.com/45th/mokumegane.html

Mokume Gane Wedding Rings: Reddot & iF Design Award READ MORE >>

Mokume Gane Engagement Rings READ MORE >>

Mokume Gane Wedding Bands READ MORE >>

Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 21 : Japanese family crest, the roots of a logo monograms

CRESTS

Among the crests that have been handed down for generations in Japan, there are family crests that are now being used as logos.

Among the Kozuka owned by Mokumeganeya, there are some from the Edo period with family crests.

The origins of family crests go back to the aristocratic society of the Heian period, when natural motifs came to be used decoratively in clothing and furniture items, and repeated use of favorite patterns developed into that family’s emblem. Also, in the warlike society that preceded the Edo period, it is said that they were used to tell different Daimyo warlords apart, and to differentiate between friend and foe on the battlefield. Patterns were used that were simple and easy to distinguish from a distance. And as the merchant culture of the Edo period evolved, they came to be used more widely as Kabuki actors and townspeople competed to be fashionable.

Around that period, there was also a trend to go beyond the precious family crests that had been transmitted for generations towards a broader derivative use in which they were enjoyed as ornamental patterns.

It is said that the logo monograms seen on famous overseas leather products also have their roots in these Japanese family crest derivatives.

The kozuka that was introduced above can be said to be one such example of a family crest derivative.

The two crests made of gold inlay in finely chiseled areas, stand out against the background of the complex and intricate Mokume Gane pattern.

The fan pattern is the same as the family crest of the Satake Clan of Akita Prefecture for which the originator of Mokume Gane, Shôami Denbei, worked.

One can say that depending on how it is used, Mokume Gane can be either on the frontline or in a support role in decorative arts techniques.

Mokume Gane Wedding Rings: Reddot & iF Design Award READ MORE >>

Mokume Gane Engagement Rings READ MORE >>

Mokume Gane Wedding Bands READ MORE >>

Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 20 : Various patterns of Mokume Gane

Types of Mokume Gane Pattern

The patterns of Mokume Gane are created by carving and twisting layers of metal. Because it is hand-made by craftsmen and the same patterns cannot be reproduced, each and every product can be described as unique. In this chapter, we will look at the specifics of individual pattern categories.

To start with is the Mokume Gane of the Akita Shôami school, the creators of Mokume Gane. Its particularity is the combination of diagonal stripy patterns that seem to be flowing with rounded burl-like patterns in colorful combinations of gold, silver, copper and shakudo.

The ingenious combination of carving and twisting produced patterns that made for the highly skilled early Mokume Gane.

Patterns created by Shôami Denbei are also being used in Mokume Gane jewelry and are very popular.

This is the kind of pattern most commonly seen in the Mokume Gane tsuba of the Edo period that are still in existence.

An intricate and elegant pattern was created by randomly hammering down the metal layers to flatten them.

The characteristic of the Mokume Gane made in the latter part of the Edo period by Tsunetada who lived in Bushu Kawagoe (the modern-day town of Kawagoe) was the Tamamoku pattern. Tamamoku refers to the burl pattern in wood and is a highly prized, beautiful pattern, developing layers of concentric swirls. The Tamamoku effect is achieved by carving the layers of differently colored metals into a circular shape which is then flattened. Tsunetada covered the entire surface of different-sized tsuba with Tamamoku, creating vibrant patterns.

In the case of Takahashi Okitsugu who worked in Edo, his uniqueness lay in his ability to represent realistic artistic landscapes in which even the passing of time could be felt within the small surface of a tsuba. He actually showed cherry blossoms and red maple leaves floating in a river. He was the one who took Mokume Gane from a technique to create patterns to one that could represent actual images.

This distinctive pattern by Okitsugu came to be used in the Mokume Gane tsuba seen in the latter part of the Edo period. The irregular superimposition of carved fine, vertical stripes resulted in a regular pattern, making Mokume Gane technique entirely into a technique for patterns.

We will conclude by introducing a very important Mokume Gane pattern.

The Shôami school spread and was active nationwide, and among these, Shôami Morikuni, a tsuba manufacturer of Iyo (the current Ehime Prefecture) left a rare square crest pattern for posterity. The pattern was achieved in the standard Tamamoku manufacturing method by carving down layered metal, but the surface of the tsuba is covered irregularly with both large and small square shaped crest patterns, giving a bold and virile impression. This is a very particular pattern of which there are no other examples.

It is said that Mokume Gane patterns are born of the conversation between the craftsman and the metal. Each and every pattern that is born of the combination of the intention of the maker and randomness is unique in the world.

Mokume Gane Wedding Rings: Reddot & iF Design Award READ MORE >>

Mokume Gane Engagement Rings READ MORE >>

Mokume Gane Wedding Bands READ MORE >>

Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 19 : Modern Mokume Gane made by using precious metal

The Use of Precious Metals in Mokume Gane

With the shift in the use of Mokume Gane which was made from gold, silver, copper, copper alloys in the Edo Period, to current times when it is used for decorative purposes, it was essential to transition to precious metals such as various colors of gold and platinum. This is because of the disadvantage in the loss through friction on copper alloys of the colors that are achieved with thin films that are applied to the surface using boiled color patination.

Mokumeganeya representative director TAKAHASHI Masaki obtained his doctoral degree on the subject of Mokume Gane. We will introduce here an outline of the portion of his doctoral thesis, “The Possibilities of Decorative Expressions in Mokume Gane Jewelry”, on the possibilities of precious metals in Mokume Gane.

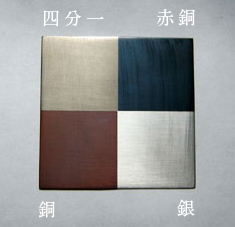

In the second chapter of this PhD thesis, these decorative effects were verified by manufacturing color samples in which precious metals were substituted in the pattern on an Edo period tsuba that he had already reproduced. As a result, the first thing that became clear was the possibility of a new technology to naturally blend the hues of different metals in Mokume Gane. The colors of the precious metals that are frequently used in jewelry are gradations of gold, silver and copper. Mokume Gane could in fact bring out intermediate nuances.

The next point which was addressed is the renewed perception of the depth of Mokume Gane’s essence, which is a construction of patterns by interweaving materials. In producing the color samples by substituting precious metals, the combinations made it so that where the shades of adjoining precious metals were close, it was not possible to see the differences in pattern with the naked eye. Therefore, a method was developed to better define the color boundaries and enhance the decorative effect through a very slight corrosion of the metals. By enhancing definition through corrosion of Mokume Gane which is created by twisting, carving and then flattening the metal materials, a construction can be achieved that creates a pattern in which the interwoven metals support and bring out one another, creating a new outlet for the energy that is inside.

The slight difference in elevation brought about by the corrosion does not just have the effect of defining the shades in color more clearly, but also shows the undulations of the boundaries according to the order of the layering, which is a clear record of the time involved in the manufacturing process.

One could say that the patterns in the Mokume Gane jewelry made with precious metals represent both the intricate colors and also the time it has taken to achieve them.

Mokume Gane Wedding Rings: Reddot & iF Design Award READ MORE >>

Mokume Gane Engagement Rings READ MORE >>

Mokume Gane Wedding Bands READ MORE >>

Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 18 : Mokume Gane made by using uniquely Japanese alloys

Rôgin/Oborogin and Karasugane/Ukin

These are names of metals from Japan’s past. They refer to colors. They achieve something similar to the delicate nuances of color found in nature. They speak of the refinement of the Japanese who found so many different names for them.

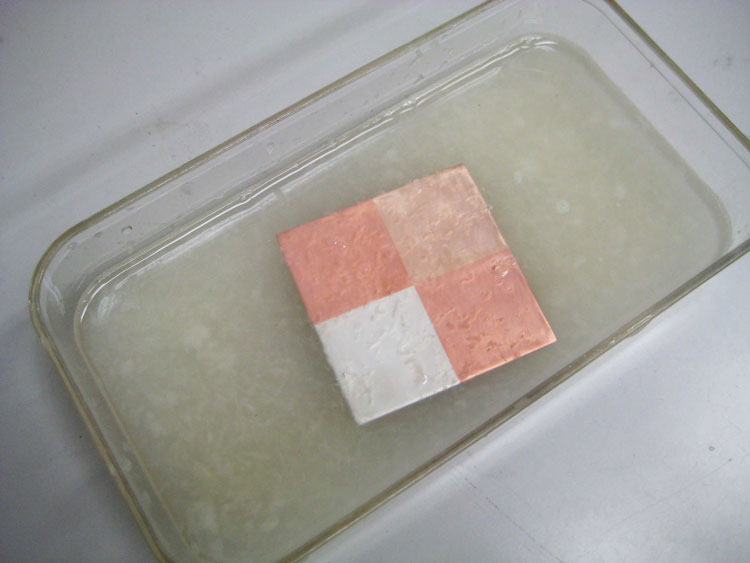

During the Edo period, in addition to gold, silver and copper, mokume-gane was made using uniquely Japanese alloys such as shibuichi and shakudo. Patterns could be created thanks to the differences in color of these metals. Since, in their raw state, these copper alloys look no different from copper, it is hard to see the difference when they are layered with silver and copper and twisted or carved. It is with the final traditional technique known as boiled color patination that the color changes and that the intricate mokume-gane pattern becomes visible.

“Oborogin” is the name given to shibuichi after the boiled color patination. The term “Oboro” comes from “Oborotsukiyo” which refers to spring nights with a hazy moon, resonating with the actual color. The name suggests a layer of mist upon a brightly shining moon. The alloy consists of one part silver to three parts copper. “Karasugane” is another name for shakudo. The name comes from the resemblance to a crow’s feathers when wet. It is an alloy of copper and gold, with the proportion of gold varying from 1% to 5%.

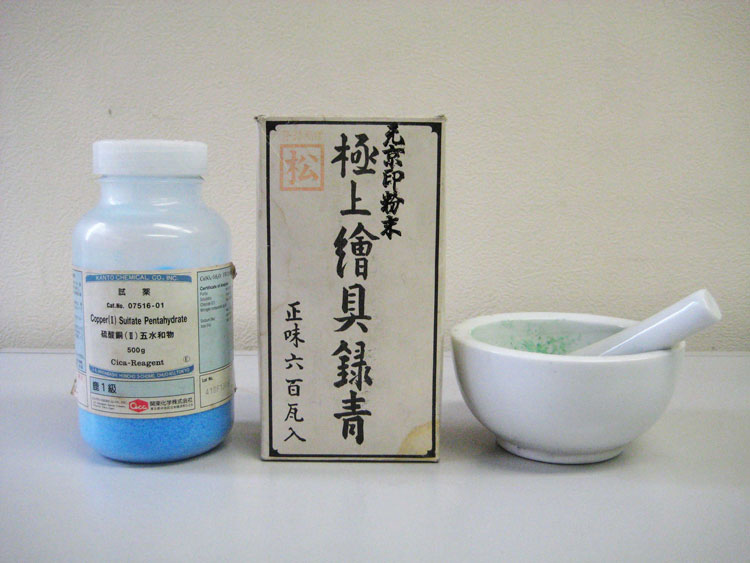

Boiled color patination is a method whereby copper sulphate and Rokusho pigment are mixed with water, brought to the boil, and then boiled until the color is achieved.

When the boiling process is carried out, the surface must be polished so that there is not even the slightest irregularity nor any oxide film. To achieve this, the alloy is dipped, just before boiling, in water mixed with finely grated daikon radish, a method that has been transmitted unchanged from olden times.

The patinated alloy that has changed color has a thin film on its surface. You could say that it is a rusted surface. If this thin film is rubbed too hard, it will gradually disappear, so it is covered with either wax or a thin film of transparent paint. This is what makes it a challenge to use in modern jewelry.

At Mokumeganeya, we have been working on developing our technology in using gold and platinum, rather than copper alloys, in order to enhance the attractiveness of mokume-gane in modern times. Since the pattern is produced by the colors of the actual metals that are used, our aim is for mokume-gane patterns that you will be able to enjoy each and every day as you wear the pieces. We are making further efforts with regard to the layering of these precious metals, and that is what we will be discussing in our next chapter.

Mokume Gane Wedding Rings: Reddot & iF Design Award READ MORE >>

Mokume Gane Engagement Rings READ MORE >>

Mokume Gane Wedding Bands READ MORE >>